Autobiographical Memory

6 minute read

During the autumn of 2020 I started a three month internship within the psychology department with Prof. Richard Roche. Richard’s research interests are in cognitive neuroscience/neuropsychology, particularly memory, ageing, dementia, stroke, brain injury and synaesthesia. During this internship I worked on several different projects but primarily focused on the of brain regions associated with autobiographical memory.

Autobiographical Memory

Memory can be seen as the means by which we draw information from our past experiences in order to use in the present. It’s a multifaceted concept, supported by various theories, yet at its core, memory involves three fundamental stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. Delving deeper, we encounter a spectrum of memory types, including sensory memory, short-term memory, working memory, and long-term memory, each playing a distinct role in how we process and retain information.

Among these, autobiographical memory (ABM) is a fascinating and complex facet of human cognition. It refers to a memory system that consists of episodes recollected from an individual’s life, which are based on a combination of episodic memory (personal experiences and specific objects, people, and events experienced at particular times and places) and semantic memory (general knowledge and facts about the world).

To understand autobiographical memory’s structure, Conway and Rubin (1993) proposed a hierarchical framework consisting of three levels:

- Lifetime Periods: This level captures extensive spans of time, often stretching over years, such as childhood or adolescence. It’s characterized by thematic memories that define these eras, like school days or early career experiences.

- General Events: A step down in the hierarchy, this level includes memories of experiences that may last days, weeks, or years. Examples include recurring activities like annual family vacations or the process of learning a new skill.

- Event-Specific Knowledge: At the most granular level, this category holds detailed memories of particular moments, such as the joy of a graduation ceremony or the emotions felt on a wedding day.

Brain Regions

When it comes to the brain and ABM, activation is typically seen as being more left lateralized, with some activation seen in the right hemisphere. A meta-analysis by Svoboda and colleagues (2006) examined 24 imaging studies to quantify this asymmetry. They calculated a Cortical Activation Ratio (CAR), where a value of 1 would signify symmetrical activation across both hemispheres. Their findings revealed a CAR of 1.81, suggesting nearly double the number of activation coordinates in the left hemisphere compared to the right.

Further analysis differentiated between medial and lateral subcortical regions. The medial regions showed a CAR of 1.73, while the lateral subcortical regions had a CAR of 1.46. These ratios underscore the left hemisphere’s predominant role in ABM, particularly within the medial and subcortical areas. This lateralization highlights the intricate interplay between different brain regions in the orchestration of ABM.

Prefrontal Cortex

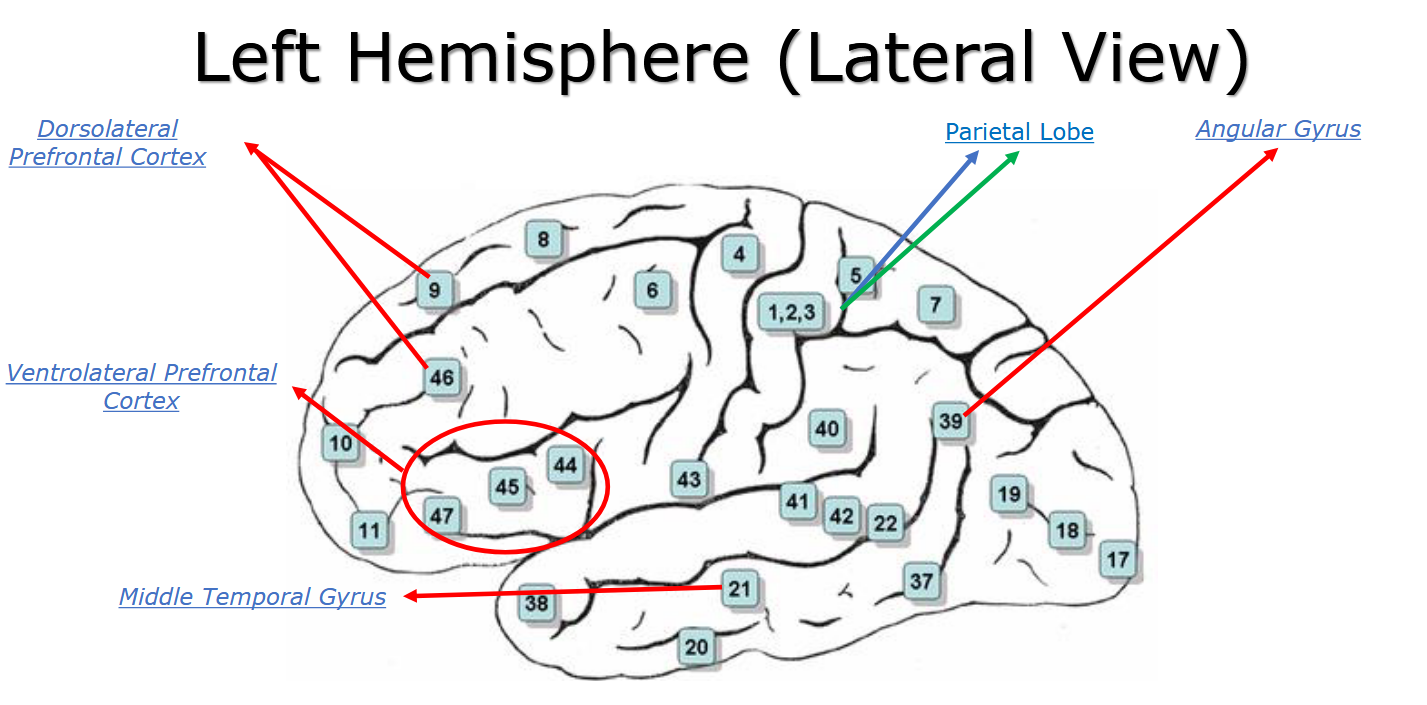

When breaking down these activation ratios into specific areas, the frontal lobe, particularly the prefrontal cortex, is one of the key areas noticed in many of the studies. The prefrontal cortex comprises distinct regions: the dorsolateral (BA 8, 9, 10, 46), ventrolateral (BA 44, 45, 47), medial (BA 12, 25), and ventral (BA 11, 13, 14) areas. Neuroimaging studies often show these regions, particularly on the left side of the brain, are active during memory tasks. While it’s known that they form a network for memory retrieval, it’s unclear if they are specifically tuned to ABMs or general memory due to varying study methodologies (Maguire, 2001).

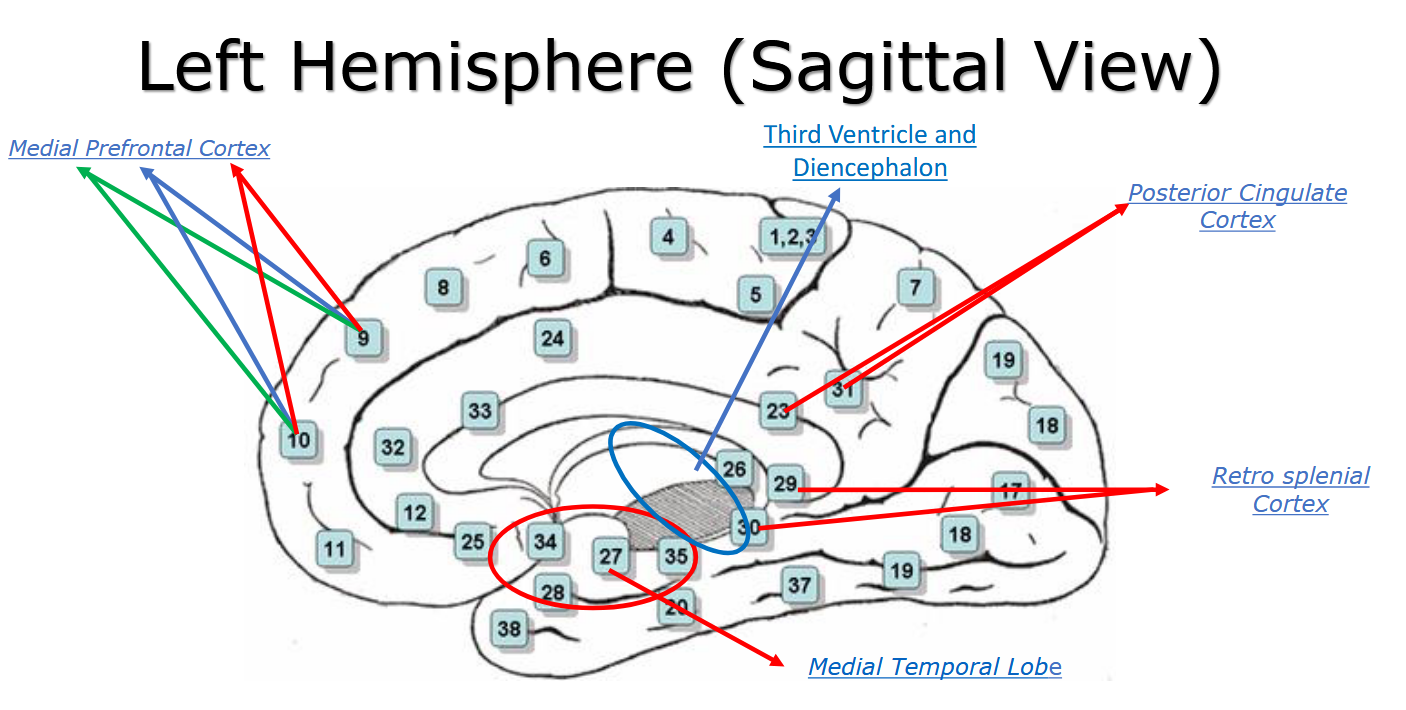

Additionally, the medial prefrontal cortex, along with the hippocampus, has been identified as particularly responsive to ABMs. Studies show that patients with amnesia or damage to the medial prefrontal cortex can remember and construct detailed events but struggle to place themselves within those past events (Kurczek et al., 2015; Levine et al., 2009). This might be because the ventromedial part of the medial prefrontal cortex helps attach personal significance and emotional intensity to memories, which are crucial for recalling oneself in past experiences. Additionally, this region is more active when recalling happy autobiographical memories compared to neutral ones.

Furthermore, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is implicated in the initial construction of less rehearsed ABMs. This region, along with the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, contributes to the formation of ABMs, although it may also be involved in constructing general memories due to varying research methods. The ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is crucial for retrieving ABMs, including the retrieval and verification of memories. It supports the mental time travel associated with ABM recall through elaboration and self-cueing during narrative recall. While both regions are primarily activated in the left hemisphere, the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is specifically active when recalling images during ABM retrieval.

Temporal Lobes

The temporal lobes, much like the frontal lobes, are integral to ABM, with a majority of studies indicating left-sided activation. Key areas within the temporal lobes include the medial temporal lobe, which houses structures like the amygdala and hippocampus, crucial for encoding and later retrieving memories.

Two main theories debate the role of the medial temporal lobe in ABM:

- Standard Consolidation Model: Suggests that after memories are consolidated, the medial temporal lobe (excluding the hippocampus) is involved in retrieving less frequently recalled ABMs (Múnera et al., 2014).

- Multiple Trace Theory Model: Argues that the medial temporal lobe is always involved in retrieving remote ABMs, regardless of consolidation (Moscovitch et al., 2006).

Research indicates that the vividness, detail, and personal significance of ABMs can influence hippocampal and medial temporal lobe activity during recall. Additionally, the ABM network involves the retrosplenial cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, which facilitate retrieval by communicating with other brain regions. The temporal pole and temporoparietal junction also play roles in transforming information and are implicated in ABM processes, with damage to these areas affecting memory recall.

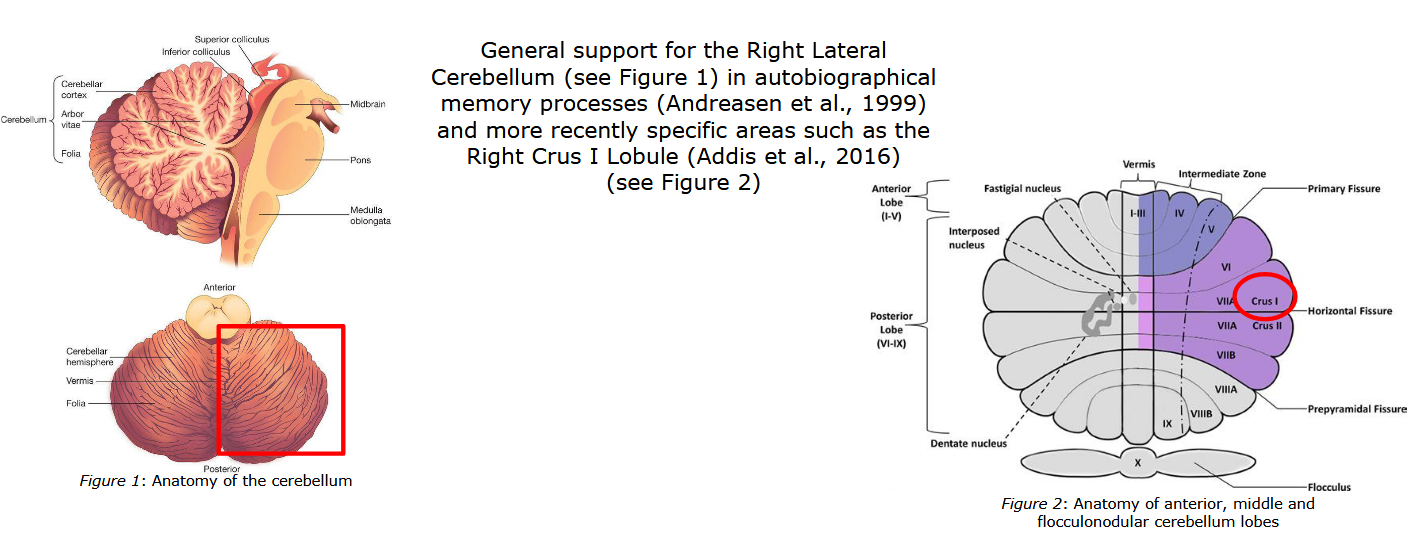

Cerebellum

The cerebellum, nestled in the posterior cranial fossa, is another key brain region linked to ABM. Unlike the frontal and temporal lobes, cerebellar activity related to ABM is mainly right lateralized, particularly in the right Crus I lobule. While its precise role in ABM is still being explored, prevailing theories suggest the cerebellum supports the retrieval of ABMs. It may function in concert with the anterior cingulate cortex and thalamus, contributing to verbal recall or memory components. Recent studies, including one on an individual with “Highly Superior ABM”, indicate cerebellar involvement when accessing and verbally elaborating upon ABMs (Mazzoini et al., 2019).